There Are No Mahayana Monasteries

At least, not in the way we think

Photo by Raju Kumar on Unsplash

Introduction

It has become all too common these days to refer to Buddhist monasteries (by which I mean established communities of monks or nuns that maintain traditional Vinaya observance) by their cultural flair or the doctrinal views they follow. We may call some monasteries “Tibetan”, or “Zen”, “Theravāda”, or even “Mahāyāna” or “Hīnayāna” (i.e. Śrāvakayāna). While it may seem to make sense, these labels create unnecessary barriers between monastics who are actually much closer spiritual siblings than it may appear. Moreover, they obscure an underlying truth about how so-called Mahāyāna monasteries function.

The reason why I wrote this article is twofold. Firstly, it is to challenge misconceived notions about monasticism that I have encountered throughout my time in Buddhist circles. Secondly, it is to demonstrate why the remaining Vinaya lineages should cooperate and support each other far more than they currently do—not just for practical benefits, but for the very survival of Buddhism itself.

One such fundamental misconception is that contemporary monastics following Mahāyāna have their own “Mahāyāna” Vinaya that has been adapted to this tradition. In fact, such misconception is not surprising given the observable differences in how many Mahāyāna monastics behave compared to their Theravāda counterparts (the reasons behind these differences will become apparent later in the article). This misconception extends further to individual subschools of Mahāyāna, leading to mistaken ideas such as that Tibetans have their own endemic Vinaya lineage.

Now, I am not saying that Tibetan monasteries are not Mahāyāna, because doctrinally speaking, they certainly are. However, when we examine what we call “Mahāyāna” monasteries we discover something quite surprising to many: they are, institutionally speaking, Śrāvaka communities that happen to study and practice based on Mahāyāna literature. The daily activities, ethical rules, and community structures that define monastic life remain fundamentally Śrāvaka, regardless of which sūtras are studied or which philosophical positions are emphasised.

Nevertheless, for these communities it is precisely these doctrinal elements that identify them as Mahāyāna, while the institutional affiliation remains largely unrecognised or considered secondary. This distinction between institutional and doctrinal layers is the focal point of this article—by understanding these categories, the question of whether there really are Mahāyāna monasteries becomes simply a matter of which layer one is addressing.

This understanding has profound practical implications that extend far beyond academic categorisation. As someone living within this tradition as a bhikshu, I’ve witnessed firsthand how these categorical confusions create unnecessary divisions between communities that share fundamental structures and practices. The most striking of these divisions occurs between Tibetan and Theravāda monastics, despite their remarkably similar institutional foundations.

Therefore, I believe that understanding this relationship could fundamentally change how Buddhist communities relate to each other, potentially bridging sectarian divides that exist primarily out of misunderstanding rather than genuine incompatibility. In the following sections, I will examine these practical questions of ordination recognition, institutional cooperation, and the very survival of both Mahāyāna and Buddhism as a whole in the modern world—demonstrating that cooperation between these traditions is not merely beneficial, but essential.

Why Tibetan Monastics Are Śrāvaka

First, it’s essential to clarify what we mean by “Śrāvaka.” The term literally means “hearers” or “listeners”—those who received the Buddha’s teachings directly and sought to implement them for their own liberation. The Śrāvakayāna, or “Vehicle of the Listeners,” represents the Buddha’s foundational teachings aimed at practitioners who wish to escape saṃsāra as swiftly as possible through individual effort. In this vehicle, the primary understanding is that desire, craving, and attachment are the root causes of our cyclic existence and suffering, and by systematically eliminating these mental afflictions through ethical conduct, mental absorption, and wisdom, one attains nirvāṇa—the cessation of suffering.

The Śrāvaka path further emphasises personal liberation through following the Prātimokṣa vows (prāti meaning individual, and mokṣa meaning liberation), which are included in the Vinaya Piṭaka. Crucially, the entire Vinaya system—the monastic code, ordination procedures, community governance structures, and disciplinary frameworks—was established specifically for this Śrāvaka path of individual liberation. This Śrāvaka institutional framework forms the foundation upon which all Buddhist monastic communities are built, regardless of their later doctrinal developments or philosophical orientations.

Now consider a typical day in what most people would call a “Mahāyāna monastery” in the Tibetan tradition. The monastics wake before dawn, wash, gather for prayers before breakfast, and some eat their final meal before noon—following the Prātimokṣa prescription against eating after midday. Every full-moon and new-moon, they perform the poṣadha ceremony (uposatha in Pali, and sojong in Tibetan) in which they confess their transgressions, and renew their vows.

Just like in Theravāda monasteries, they maintain the essential poṣadha structure, though with some variations in practice. For instance, in some Theravāda communities, monks must confess any disciplinary violations to another monk or the Saṅgha before the Pāṭimokkha recitation, maintaining the Buddha’s original emphasis on purification before the ceremony.1 While Tibetan monastics follow the same confession procedure, they do so as a group rather than individually.

Moreover, during the summer months, they observe the three-month rain retreat (varṣā in Sanskrit, vāsa in Pali, and yarne in Tibetan), where they take the varṣā vows at the starting ritual and release them at the end of the intensive study and meditation period in between. However, while the Theravādins ubiquitously do the retreat for 3 months, many Tibetan monasteries have halved it due to lack of a heavy rainy season in Tibet.

Tibetan monasteries also have disciplinarians (vinayadhara) who enforce rules, abbots (mahācārya) who lead and manage the monastery, and chant masters who lead liturgical functions. In short, their entire yearly and daily schedule operates according to a Vinaya structure that they inherited from India and has remained essentially unchanged for over two millennia. The name of this lineage is the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya.

For those not acquainted with this Vinaya tradition, it is an offshoot of the Sthavira Vinaya, one of the first distinctive Vinaya lineages that emerged from the Second Buddhist Council. Notably, the Theravāda itself also derived from this same Vinaya, making them close cousins. The Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya was then brought to Tibet at various times and by various Indian monastics from North India throughout the Tibetan translation period.

Having a common root, both traditions maintain the same fundamental Vinaya framework - the core structure of vows and precepts, community governance, and ceremonial observances - though their practical expression varies between cultures. While Theravāda communities maintain stricter adherence to practices like piṇḍapāta (alms rounds) and additional observances, and Tibetan monastics have adapted to different cultural and geographical contexts, both operate within recognizably Śrāvaka institutional structures.

Tibetan monks in Dharamshala, courtesy of Norbu Gyachung.

In other words, their institutional backbone is thoroughly and unmistakably Śrāvaka. Even so, many monastics aren’t aware of this or haven’t been taught the historical distinction between institutional affiliation (sect) and doctrinal orientation (school)2, leading to understandable confusion about their identity. Some don’t know they follow Śrāvaka institutional structures, while others resist being called “Śrāvaka” because they want to be seen as Mahāyāna, not realising that these categories operate on different dimensions entirely.

This misunderstanding has real and sometimes negative consequences. When Tibetan monastics encounter Theravāda communities, they’re often treated as institutional foreigners despite sharing remarkably similar Vinaya traditions. Since they both emerged from the Sthavira Vinaya, they share far more institutional DNA than their modern categorical separation would suggest. The same can be said about the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya in East Asia. In fact, the Mūlasarvāstivāda is slightly stricter given that it contains mostly the same vows that the Theravāda Vinaya has (give or take a handful) while containing 26 more.3

Yet institutional barriers persist. Theravāda monks may refuse to share activities with their Tibetan counterparts or decline to share food with them, treating them as followers of an alien tradition. The irony is that some Theravāda communities differ significantly from others in doctrinal emphasis yet remain institutionally unified, while Tibetan monastics with closely related institutional practices are treated as foreigners. For instance, some Theravāda communities study Abhidhamma literature extensively, which is a sharp contrast to traditions such as the Thai Forest Tradition, which gives Abhidhamma minimal importance.

Meanwhile, Vietnamese communities like those inspired by Thich Nhat Hanh follow their Dharmaguptaka Vinaya so carefully that Theravāda monks might readily share food and even robes with them, despite being doctrinally Mahāyāna. Given that the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya is historically just as close to Theravāda as the Dharmaguptaka tradition, we would expect more institutional cooperation between these schools. So how is it that some Vinaya lineages come to be linked with Mahāyāna while others didn’t? To answer this we first need to define what exactly is Mahāyāna.

What, If Anything, Is Mahāyāna?

This question, as a reference to scholar Jonathan Silk’s influential study, cuts to the heart of our categorical conundrum.4 Silk and other researchers have explained that Mahāyāna was never an institutional category in ancient India. Instead, it was a doctrinal, literary and practice-based movement that spread across existing monastic sects, much like a religious revival that influenced multiple types of monastic institutions without creating new institutional structures (however, it is worth mentioning that while Tibetans claim that there once existed a purely Mahāyāna Vinaya, no scriptures or evidence has surfaced till date).

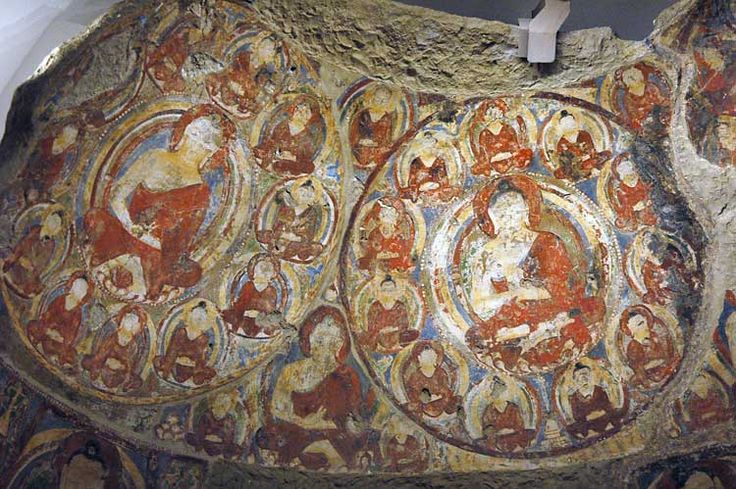

Paintings of Bamiyan Valley.

The crucial distinction here was first clearly articulated by Louis de La Vallée Poussin nearly a century ago. Buddhist sects (nikāya) were defined by their Vinaya—their monastic rules, ordination lineages, and institutional procedures. Schools (vāda), on the other hand, were defined by doctrinal characteristics, philosophical positions, and interpretive approaches to Buddhist teachings.5 A monastery’s sectarian or institutional identity was determined by which Vinaya its monks followed and from whom they received ordination, not by which sūtras they studied, which philosophical positions they held, or which meditation practices they emphasised.

La Vallée Poussin observed that one enters a nikāya or sect through a formal ecclesiastical act of ordination (upasampadā karmavācanā), creating an institutional identification that cannot be changed without re-ordination. Schools, by contrast, represent intellectual and spiritual affiliations that can evolve throughout a monastic’s career. A monk might study Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma in his youth, encounter Madhyamaka philosophy in middle age, and practice Pure Land devotions in old age, while maintaining the same sectarian identity throughout his life.

In fact, historical evidence strongly supports this institutional interpretation. The Chinese pilgrim Yijing, who spent over two decades throughout India and Southeast Asia, wrote in 691 CE what may be our clearest ancient definition of the Mahāyāna-Hīnayāna distinction: “Those who worship the Bodhisattvas and read the Mahāyāna Sūtras are called the Mahāyānists, while those who do not perform these are called the Hīnayānists.”6 Crucially, Yijing noted in the same citation that individual sects could belong to either vehicle—the same monastic community might have both Mahāyāna and non-Mahāyāna practitioners under the same roof.

As the nineteenth-century scholar Junjirō Takakusu observed in his translation of Yijing’s work, “I-Tsing’s statement seems to imply that one and the same school adheres to the Hīnayāna in one place and to the Mahāyāna in another; a school does not exclusively belong to the one or the other.”7

Auguste Barth, analysing Yijing’s observations in detail, concluded that “there were Mahāyānists and Hīnayānists in all or in almost all the schools.”8 He described Mahāyāna as “a religious movement with rather vague limits, at the same time an internal modification of primitive Buddhism and a series of additions to this same Buddhism, alongside of which the old foundations were able to subsist more or less intact.”

Jean Przyluski extended this analysis, arguing that rather than representing a single institutional development, Mahāyāna should be understood as multiple concurrent movements: “One can also speak, up to a certain point, of a Sarvāstivādin Mahāyāna, a Mahāsāṅghika Mahāyāna, and so on.”9

This scholarly consensus suggests that terms like “Mahāyāna monastery” represent category errors. What we’re actually describing are Sarvāstivāda monasteries that study Mahāyāna literature, or Dharmaguptaka monasteries that practice Bodhisattva ideals, or Mūlasarvāstivāda monasteries that emphasise Madhyamaka philosophy.

The situation becomes clearer when we consider it through the lens of what Kenneth Bailey calls “polythetic classification”—a method that allows objects to be grouped based on shared characteristics without requiring any single feature to be present in all members of the group.10 Rather than forcing Buddhist communities into rigid either/or categories, we can recognise that they participate in multiple overlapping traditions simultaneously.

How Śrāvakayāna and Mahāyāna Coexist

The Buddha himself anticipated this institutional flexibility. In the Ārya Vinaya Viniścayopāli Paripṛcchā Nāma Mahāyāna Sūtra (The Noble Mahāyāna Sūtra “Determining the Vinaya: Upāli’s Questions”), he explained how bodhisattva training differs from—yet builds—upon śrāvaka training:

Upāli, […] followers of the Śrāvakayāna do not even have the fleeting desire to take rebirth in the world. [Yet,] bodhisattvas who follow the Mahāyāna take rebirth in saṃsāra for countless eons without aversion or weariness. […] Upāli, bodhisattvas who follow the Mahāyāna should work with the minds of other beings and other people, while the followers of the Śrāvakayāna do not need to. Upāli, that is why the training of bodhisattvas who follow the Mahāyāna guards, while the training of the followers of the Śrāvakayāna does not guard.

The sūtra reveals that whilst the Śrāvakayāna places particular importance on the extinction of desire, as it is seen as the cause of suffering, the Bodhisattvayāna places utmost importance on extinguishing anger instead. The reason being, as the Buddha explains, “anger forsakes beings, whereas desire brings beings together”. Nevertheless, this isn’t about changing monastic rules—it’s about understanding them through a different soteriological lens within the same institutional framework. The Mahāyāna sūtras place significant importance on Vinaya precisely because it provides a systematic means of accumulating merit that becomes the bodhisattva’s resource for benefiting beings across lifetimes.

The First Council. Mural painting in the Nava Jetavana temple, Jetavana Park, Uttar Pradesh, India, late 20th century. Courtesy of Photo Dharma from Penang, Malaysia

What Buddha means by “the training of bodhisattvas who follow the Mahāyāna guards” becomes more apparent later in the sūtra. He elaborates on how bodhisattva precepts function as a “remedy” that works alongside, not instead of, traditional monastic discipline:

If a bodhisattva who follows the Mahāyāna commits a fault in the morning and does not part from [bodhicitta] the omniscient mind at midday, then the complement of ethical discipline of the bodhisattva who follows the Mahāyāna is not at all inhibited… Therefore, Upāli, the training of bodhisattvas who follow the Mahāyāna serves as a remedy.

This means that a bodhisattva who maintains bodhicitta can recover quickly from ethical lapses, whilst śrāvaka training becomes ’exhausted’ through repeated faults. Cultivating bodhicitta essentially protects a Mahāyāna monastic’s conduct, keeping their precepts intact. This teaching, later expanded upon by Sakya Pandita in his “A Clear Differentiation of the Three Codes”, is one of the main reasons why Tibetan monastics’ behaviour differs from that of their Theravāda cousins, though this teaching requires careful interpretation to avoid undermining the foundational importance of Vinaya discipline.

Moreover, it demonstrates that what we call “Mahāyāna monastics” are actually śrāvaka monastics who have taken additional bodhisattva vows. They remain structurally Śrāvaka—following the Prātimokṣa, living by Vinaya rules, participating in poṣadha ceremonies, maintaining ordination lineages—whilst aspiring towards the Mahāyāna ideal of universal liberation.

La Vallée Poussin captured this relationship precisely: “From the disciplinary point of view, the Mahāyāna is not autonomous. The adherents of the Mahāyāna are monks of the Mahāsāṅghika, Dharmaguptaka, Sarvāstivādin and other traditions, who undertake the vows and rules of the bodhisattvas without abandoning the monastic vows and rules fixed by the tradition with which they are associated on the day of their Upasampadā.”11

He further observed: “All the Mahāyānists who are pravrajita [renunciants] renounced the world entering into one of the ancient sects.—A monk, submitting to the disciplinary code (Vinaya) of the sect into which he was received, is ’touched by grace’ and undertakes the resolution to become a buddha. Will he reject his Vinaya?—‘If he thinks or says “A future buddha has nothing to do with learning or observing the law of the Vehicle of Śrāvakas,” he commits a fault of pollution (kliṣṭa āpatti).’”12

Think of it this way: if institutional structure is like the skeleton of a body, then the Śrāvaka Vinaya provides the bones that give shape to monastic life. Whether that body has “Mahāyāna skin” or “Abhidhamma skin” is, in some sense, surface detail. The fundamental architecture—the daily rhythms, ethical framework, community structures, and ordination lineages—remains recognisably and necessarily Śrāvaka.

A good example of this principle is the ancient University of Nālandā, where Mahāyāna philosophy flourished within a rigorous Vinaya environment. The archaeological remains show dormitories arranged according to traditional Vinaya requirements, assembly halls for poṣadha ceremonies, and the same institutional rhythms that governed any śrāvaka monastery. When scholars like Virūpa (9th century CE) and Maitripa (11th century CE) began incorporating tantric practices that violated Vinaya standards, they were expelled—not because their Mahāyāna philosophy was problematic, but because institutional discipline remained the highest priority. The institution could accommodate diverse doctrinal orientations but not violations of its Śrāvaka foundation.

This understanding helps explain why contemporary “Mahāyāna” monastics can struggle with identity questions. They practise śamatha meditation as described in both Śrāvaka and Mahāyāna texts, follow Vinaya rules established in early centuries, and participate in institutional structures that predate Mahāyāna literature by centuries. Yet they also study Prajñāpāramitā sūtras, cultivate bodhicitta, and aspire to Buddhahood for the benefit of all beings. Rather than representing contradictory affiliations, these practices reflect the historical norm: Śrāvaka institutional foundations supporting diverse spiritual aspirations.

Theravādin Mahāyāna in Sri Lanka

The artificial nature of our contemporary Buddhist categories becomes even clearer when we examine one of the most remarkable yet underappreciated chapters in Buddhist history: the eight centuries when Theravādin Mahāyāna was the dominant form of Buddhism in Sri Lanka.13 14 This isn’t simply an interesting historical footnote—it’s powerful evidence that the institutional compatibility I’m arguing for was once the lived reality for thousands or millions of practitioners.

Sri Lankan monks, courtesy of Sidath Vimukthi.

Most contemporary Buddhists, whether Theravāda or Mahāyāna, remain unaware that what we now call “Theravāda Buddhism” actually encompassed three distinct subdivisions throughout most of Sri Lankan Buddhist history: the Mahāvihāra, Abhayagiri, and Jetavana traditions.15 All three were initially based in Anuradhapura, the ancient capital, and all three followed Theravāda Vinaya and maintained Theravāda ordination lineages. Yet the Abhayagiri and Jetavana traditions were thoroughly Mahāyāna in their doctrinal orientation and practice.

The Mahāvihāra tradition, which modern Theravāda considers its primary ancestor, was actually the smallest and least influential of the three for most of this period. According to the historical records, they were the ones who considered Mahāyāna doctrines such as Lokottaravāda (“transcendentalism”) as heretical and viewed Mahāyāna sutras as counterfeit scriptures.16 But they were the minority position, not the mainstream.

During the reign of King Mahasena (277-304 CE) who supported Mahāyāna Buddhism, the Theravāda Mahāvihāra tradition was actively repressed when they refused to accept Mahāyāna teachings. Mahasena went so far as to destroy buildings of the Mahāvihāra complex to build up Abhayagiri and establish the new Jetavana monastery. Following this royal intervention, Abhayagiri emerged as the largest and most influential Buddhist tradition on the island.17 The Mahāvihāra tradition would not regain its dominant position until the Polonnaruwa period in 1055 CE—over seven centuries later.

When the Chinese monk Faxian visited Sri Lanka in the early 5th century, he found clear evidence of this institutional diversity thriving within shared frameworks. He noted 5,000 monks at Abhayagiri, 3,000 at the Mahāvihāra, and 2,000 at the Cetiyapabbatavihāra.17 Crucially, Faxian described Mahāyāna and Śrāvakayāna monastics living side by side in these monasteries, sharing facilities whilst pursuing different doctrinal emphases.

This coexistence continued to flourish and expand. By the 8th century, both Mahāyāna and the esoteric Vajrayāna forms of Buddhism were being practised openly within Sri Lankan Theravāda institutions. Two Indian monks responsible for propagating Vajrayāna Buddhism in China (which then moved to Japan and became the Shingon School), Vajrabodhi and Amoghavajra, visited the island during this time and found thriving Vajrayāna communities operating within Theravāda monastic frameworks.17 Abhayagiri remained an influential centre for the study of Theravāda Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna thought from the reign of Gajabahu I until the 12th century, hosting important Buddhist scholars working in both Sanskrit and Pāli.

The key point that revolutionises our understanding is this: these weren’t “Mahāyāna monks” who happened to be in Sri Lanka—they were Theravāda monks who practised Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna. They followed the same Theravāda Vinaya, participated in the same ordination lineages, observed the same institutional rhythms, and maintained the same community structures as their Mahāvihāra colleagues. This wasn’t an uncomfortable compromise—it was how Theravāda Buddhism functioned for the majority of its Sri Lankan history.

Contemporary Implications

This historical reality demolishes several contemporary assumptions. First, it shows that Mahāyāna practice is not inherently incompatible with Theravāda institutional structures—quite the opposite, it flourished within them for centuries. Second, it demonstrates that institutional foundations were strong enough to support remarkable doctrinal diversity without fragmenting into separate Vinaya institutions. Third, it reveals that what we consider “traditional Theravāda” today represents only one strand of a historically much more diverse tradition.

From my own experience in a contemporary Tibetan monastery that follows Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya while identifying as Mahāyāna, I can attest that this historical pattern of institutional unity continues. As we have discussed in the previous sections, we follow fundamentally similar institutional patterns to Theravāda communities, though our daily practices differ in various ways—they maintain stricter observances (like piṇḍapāta) while the Tibetans had to adapt these practices to different cultural and geographical contexts.

Moreover, the main difference lies not in our discipline but in our motivational framework—we embrace what the Upāli Sūtra calls the “long duration” training that allows us to remain in saṃsāra for the benefit of beings rather than solely seeking individual liberation. It is a delicate balance where the doctrinal layer of Mahāyāna is guarding the institutional layer so that rules that cannot be practiced due to the cultural context are protected.

Nevertheless, now that the Tibetan tradition has emerged from Tibet and established communities in India and the West, it may be time to re-incorporate certain practices that were lost during the cultural isolation of the plateau period. Given their shared Vinaya heritage, Theravāda communities may be ideally positioned to support such restoration efforts. Furthermore, as Theravāda monastics have successfully pioneered sustainable monastic institutions in Western contexts—maintaining rigorous standards while adapting to new cultural environments—followers of the Mūlasarvāstivāda tradition could benefit significantly from collaboration and institutional guidance from these established communities.

Going a step further, the similarities in the monastic lineage and the historical evidence open the door to a new opportunity for contemporary Buddhist cooperation: introducing the Mahāyāna tradition to Theravāda communities who wish to study and practice it alongside their existing commitments. This would solve a particular problematic consequence of our categorical confusion that happens when Theravāda monastics develop genuine interest in Mahāyāna teachings and practice. As of today they face an unfortunate choice: either suppress their Mahāyāna inclinations to maintain their Theravāda identity, or abandon their ordination lineage entirely to re-ordain in Mūlasarvāstivāda or Dharmaguptaka traditions.

However, if Theravāda Vinaya could once provide the framework for Mahāyāna and even Vajrayāna practice, then the compatibility exists in principle. The Sri Lankan precedent shows it worked in practice for centuries. A Theravāda monk interested in bodhicitta cultivation or Prajñāpāramitā study should be able to pursue these interests within their existing institutional framework, just as their Sri Lankan predecessors did. Normalising such practice would enrich both traditions whilst avoiding the disruption and spiritual cost of unnecessary re-ordination.

For Western Buddhist communities, this historical evidence is particularly relevant. Rather than viewing “Theravāda” and “Mahāyāna” as necessarily separate institutional tracks requiring distinct organisations, training programs, and teacher authorisations, we might explore how robust Śrāvaka foundations could support diverse doctrinal orientations within the same monastic institutions. A Western monastery that followed strict Vinaya discipline while welcoming both vipassanā-oriented and bodhicitta-oriented practitioners wouldn’t be an artificial hybrid—it would be recovering Buddhism’s historical norm.

Why the Śrāvakayāna Is Vital

Highlighting this coexistence and the institutional foundation of these monasteries isn’t merely historical curiosity—it may be essential for Mahāyāna’s (and Buddhism’s) survival and transmission. While this topic deserves its own article, it ties in well with highlighting the need for building good relationships between the surviving monastic traditions.

The Buddha himself was explicit about the importance of monasticism. According to the Mahāparinibbāna-sutta, he proclaimed that he would not pass away until he had established “wise, well-trained, and self-confident” members of all four assemblies: bhikshus, bhikshunīs, male lay disciples, and female lay disciples.18 The text makes this requirement unmistakably clear: having these four assemblies is what distinguishes a Buddhist tradition from other religious systems.

The Aṅguttara-nikāya reinforces this by describing the unfortunate condition of being reborn in a “border country”—defined specifically as a place where the four-fold sangha of Buddhist disciples cannot be found.19 This suggests that without proper monastic communities, a region becomes spiritually impoverished, regardless of whatever other religious activities might occur there.

The historical evidence supports what Buddha said quite clearly. Buddhism disappeared entirely from vast regions where it once flourished: Afghanistan, Pakistan, Central Asia, India, and Indonesia. These were once great Buddhist countries where you will find a great amount of archeological evidence that Mahāyāna in particular thrived there. However, despite supporting thriving Buddhist cultures for centuries, Buddhism vanished, whilst other traditions—Zoroastrianism, Hinduism, Islam, and other local beliefs that predate Buddhism—survived in the same regions.

Sri Lankan ruins, courtesy of Thushal Madhushankha.

There’s a clear pattern here when we examine the mechanism of disappearance: Buddhism’s decline invariably coincided with the collapse of monastic institutions. For instance, the demise of Buddhism in India started with the Mughal invasions destroying hundreds of Buddhist monasteries and slaughtering the monastics,20 further exacerbated by cutting their local patronage,21 alongside the appropriation and transformation of these monasteries by Brahmins who had accepted Muslim rule in exchange for the extinction of Buddhism.22 With the monastics gone, these Brahmins got their wish.

The institutional framework wasn’t just important—it was the transmission mechanism. Without ordained communities maintaining textual traditions, performing rituals, and training new generations, the entire edifice collapsed regardless of how many lay practitioners remained.

Even where Buddhist lay communities persisted for a time after monastic decline, they gradually lost access to proper teachings, ordination lineages, and institutional memory. The pattern repeats across geography and time: institutional collapse guarantees religious disappearance.

The exception that proves the rule is Newar Buddhism in Nepal, which maintained certain Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna practices without a monastic sangha. However, Newar communities remained in close proximity to Tibet, where the monastic sangha flourished vigorously. They could access institutional resources when needed, even without maintaining their own monastic communities. Remove that institutional proximity, and even the Newar example might follow the same pattern of gradual decline.

Conversely, Buddhism has demonstrated remarkable resilience where monastic institutions retained deep social roots—Tibet, Mongolia, Sri Lanka, Burma, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, China and Japan. Even during severe persecution, these traditions survived because institutional foundations remained strong enough to maintain transmission across generations. The Śrāvaka framework provided the skeletal structure that could endure political upheaval, foreign invasion, and cultural transformation.

This insight suggests something crucial for Buddhism’s expansion into new cultural contexts like the contemporary West. History shows us a clear sequence: wherever Buddhism successfully established itself, strong institutional foundations came first, then doctrinal diversity flourished afterward. Mahāyāna achieved widespread influence only after Śrāvaka monasteries had become well-established throughout the Indian subcontinent. It appears that the sequence is essential: institutional foundations first, then doctrinal elaboration.

We see this pattern repeating in the West today. Buddhist communities that have successfully established genuine monastic institutions—whether Theravāda forest monasteries, Vietnamese monasteries like Plum Village, or purely Tibetan monastic centres—show greater long-term stability than purely lay-oriented movements. Even in my short lifespan I have encountered the closing of a few Dharma centres that were for lay practitioners, as well as individual monastics themselves disrobing due to lack of a monastic community to be part of.

The key takeaway is that Śrāvaka institutional frameworks aren’t obstacles to Mahāyāna flourishing—they’re prerequisites. The Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya doesn’t constrain Tibetan monastics from studying Madhyamaka or Vajrayāna philosophy; it provides the stable foundation that makes such study possible across centuries. Similarly, if Buddhism in the West is to achieve genuine sustainability, it likely needs robust Śrāvaka institutions first, followed by doctrinal diversity emerging naturally within those frameworks.

Conclusion

In conclusion, let me revisit the title of this article and pose the question: are there any Mahāyāna monasteries? Well, doctrinally, yes. Institutionally, no—and this is the main point. By looking at it through the institutional lens, the reality is that a “Mahāyāna monastery” is a community of Śrāvaka monastics studying Mahāyāna literature and cultivating bodhicitta. And this actually represents one of Buddhism’s most successful institutional innovations—robust Śrāvaka foundations supporting diverse spiritual aspirations within their framework.

Understanding this institutional-doctrinal distinction has immediate practical consequences. The walls we’ve built between “Theravāda” and “Mahāyāna” monasteries are hindering real collaboration and sharing of knowledge and practice between both traditions. Tibetan monastics have lost practices like piṇḍapāta and daily group meditation that our Theravāda cousins, who maintain it expertly, could support in re-establishing. Meanwhile, Theravāda monastics interested in bodhicitta cultivation face unnecessary re-ordination instead of simply expanding their studies within their existing Vinaya lineage. These barriers are wasteful—we’re all working from the same basic institutional playbook.

For too long, Buddhist communities have allowed superficial categorical differences to obscure fundamental institutional similarities. Both the Mūlasarvāstivāda and Theravāda as well as Dharmaguptaka lineages trace back to the same Sthavira school, sharing remarkably similar Vinaya traditions. We share remarkably similar fundamental vows, institutional frameworks, ethical foundations, and community governance structures.

This recognition offers particular hope for Buddhism’s survival in the contemporary West, where traditional institutional transmission faces unprecedented challenges. As the Buddha explicitly warned, regions without proper monastic communities cannot sustain Buddhadharma long term—and history backs him up completely. Buddhism has vanished from every region where monastic institutions collapsed, regardless of philosophical sophistication or lay devotion. For those of us trying to establish Buddhism in new contexts, Theravāda communities are finding more success in maintaining rigorous Vinaya discipline whilst adapting to Western cultural contexts. The other lineages could learn enormously from their institutional experience, whilst sharing our own philosophical and contemplative resources developed over centuries.

The precedent for such cooperation isn’t speculative but historically proven. For eight centuries, Sri Lankan Theravāda Buddhism encompassed both Mahāyāna and non-Mahāyāna practitioners within the same institutional frameworks. The Abhayagiri and Jetavana traditions were simultaneously fully Theravāda institutionally and thoroughly Mahāyāna doctrinally. What was once normal could become normal again, particularly in cultural contexts where historical sectarian divisions carry less emotional weight.

This understanding doesn’t diminish anyone’s spiritual aspirations; rather, it reveals the elegant way Buddhist monastic institutions have always adapted to support diverse spiritual goals. A Theravāda monk committed to vipassanā meditation remains fully Theravāda. A practitioner devoted to Madhyamaka philosophy and bodhisattva ideals remains fully committed to the Mahāyāna path. But both can recognise their participation in a shared institutional heritage that transcends their particular doctrinal emphases.

Perhaps most importantly, this offers hope for Buddhism’s continued vitality in an increasingly connected world. Rather than viewing Buddhist diversity as evidence of incompatibility, we can see it as testament to the flexibility of Śrāvaka institutional foundations. The same structures that supported Abhidharma philosophy, Madhyamaka dialectics, Pure Land devotion, and Zen meditation continue to provide frameworks for contemporary adaptation.

The monastery exists. The Dharma exists. The Saṅgha exists. In recognising that there are no Mahāyāna monasteries per se—only Śrāvaka monasteries where Mahāyāna is studied and practised—we rediscover the institutional unity that could bridge our contemporary divisions. We’re all institutional siblings, following variations of the same Vinaya, trying to preserve the Buddha’s teachings for future generations. It’s time we started acting like the extended family we actually are.

Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.). The Buddhist Monastic Code, Volumes I & II. Available at dhammatalks.org/vinaya/ ↩︎

Silk, Jonathan A. “What, If Anything, Is Mahāyāna Buddhism? Problems of Definitions and Classifications.” Numen 49, no. 4 (2002): 355-405. ↩︎

Mahāmahopādhyāya Satis Chandra Vidyabhusana (trans.). “So-sor-thar-pa; or, a Code of Buddhist Monastic Laws: Being the Tibetan version of Prātimokṣa of the Mūla-sarvāstivāda School.” Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (1915). ↩︎

Silk, Jonathan A. “What, If Anything, Is Mahāyāna Buddhism? Problems of Definitions and Classifications.” Numen 49, no. 4 (2002): 355-405. ↩︎

La Vallée Poussin, Louis de. “Notes Bouddhiques XVIII: Opinions sur les Relations des deux Véhicules au point de vue du Vinaya.” Académie Royale de Belgique: Bulletins de la Classe des Lettres et des Sciences Morales et Politiques, 5e série, tome 16 (1930): 20-39. ↩︎

Takakusu, Junjirō. A Record of the Buddhist Religion as Practised in Indian and the Malay Archipelago (A.D. 671-695) by I-Tsing. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1896. ↩︎

Takakusu, Junjirō. A Record of the Buddhist Religion as Practised in Indian and the Malay Archipelago (A.D. 671-695) by I-Tsing. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1896. ↩︎

Barth, Auguste. “Le Pèlerin Chinois I-Tsing.” Journal des Savants (1898): 261-280, 425-438, 522-541. ↩︎

Przyluski, Jean. Le Council de Rājagrha: Introduction à l’Histoire des Canons et des Sectes Bouddhiques. Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1926-1928. ↩︎

Bailey, Kenneth D. Typologies and Taxonomies: An Introduction to Classification Techniques. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1994. ↩︎

La Vallée Poussin, Louis de. “Notes Bouddhiques XVIII: Opinions sur les Relations des deux Véhicules au point de vue du Vinaya.” Académie Royale de Belgique: Bulletins de la Classe des Lettres et des Sciences Morales et Politiques, 5e série, tome 16 (1930): 32-33. ↩︎

La Vallée Poussin, Louis de. “Notes Bouddhiques XVIII: Opinions sur les Relations des deux Véhicules au point de vue du Vinaya.” Académie Royale de Belgique: Bulletins de la Classe des Lettres et des Sciences Morales et Politiques, 5e série, tome 16 (1930): 25. ↩︎

de Silva, K. M. A History of Sri Lanka (2nd ed.). Penguin Books India, 2005. ↩︎

Jerryson, Michael K. The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism, page 17. Oxford University Press, 2017. ↩︎

Warder, A.K. Indian Buddhism. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 2000. ↩︎

Werner et al. The Bodhisattva Ideal: Essays on the Emergence of Mahayana. Buddhist Publication Society, 2013. ↩︎

Hirakawa, Akira. A History of Indian Buddhism: From Śākyamuni to Early Mahāyāna. Translated by Paul Groner. Motilal Banarsidass, 1993. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Dīgha-nikāya. Mahāparinibbāna Sutta (DN 16). DN II 104. Pali Text Society edition. ↩︎

Aṅguttara-nikāya AN IV 226. Pali Text Society edition. ↩︎

Eraly, Abraham. The Age of Wrath: A History of the Delhi Sultanate. Penguin UK, 2015. ↩︎

Fogelin, Lars. An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism. Oxford University Press, 2015. ↩︎

Verardi, Giovanni. Hardships and Downfall of Buddhism in India. Manohar Publishers & Distributors, 2011. ↩︎