Is the Big Bang Theory Wrong?

Challenging the Foundation of Modern Cosmology

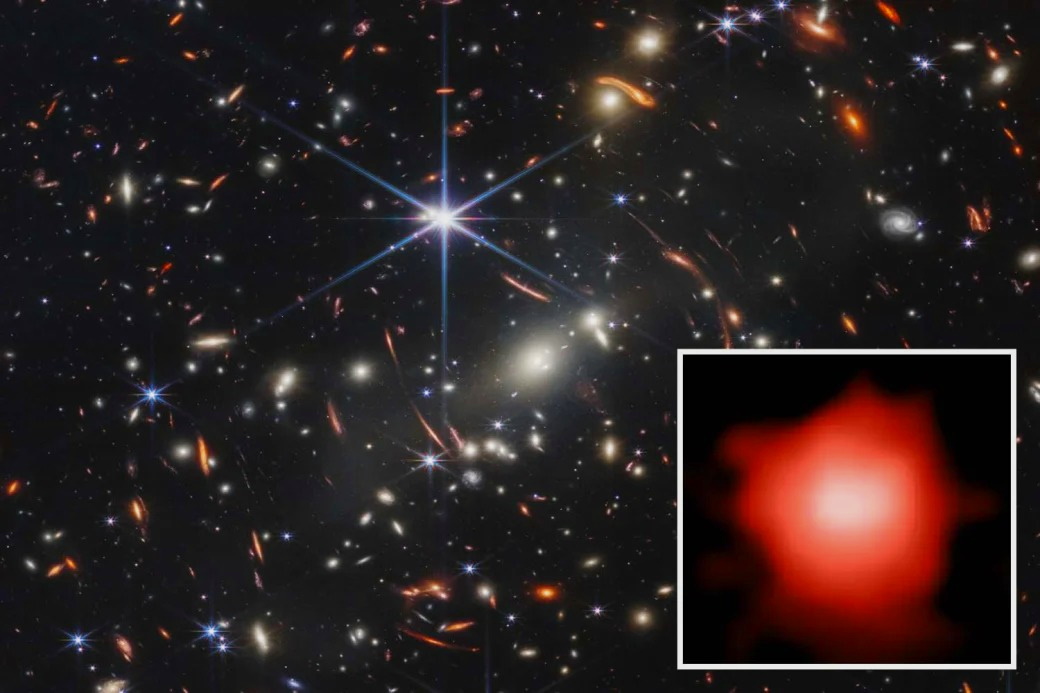

Photo by James Webb Telescope

In recent years, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has unveiled discoveries that have shaken the foundations of our cosmic understanding. Among its most startling findings are fully formed, massive galaxies dating back to just 300-500 million years after the supposed Big Bang—galaxies that, according to conventional Big Bang cosmology, simply shouldn’t exist yet. These ancient galaxies appear too large, too mature, and too numerous for the standard timeline of cosmic evolution. As Allison Kirkpatrick, an astronomer at the University of Kansas, memorably put it: “Right now, I find myself lying awake at 3 am wondering if everything we’ve done is wrong.”1

As someone who has long accepted the Big Bang Theory as an explanation for the origin of the cosmos, these findings sparked a sense of curiosity and doubt within me. However, upon deeper reflection, I realized a fundamental misconception in my understanding: the Big Bang Theory was never intended to provide an account of the true origin of the cosmos, but rather focuses on explaining the evolution of the universe from its earliest observable moments.2

This realization unveiled a common misconception stemming from our innate cognitive biases—particularly our tendency to seek definitive “beginnings” to phenomena. In this article, we’ll explore how these biases shape our understanding of cosmology, examine the influence of religious backgrounds on scientific thinking, and delve into the philosophical wisdom of the Buddhist sage Nagarjuna, whose logical framework offers profound insights into the concept of origins. Through this exploration, we aim to challenge the concept of a singular, absolute beginning and develop a more nuanced understanding of cosmic origins.

What Is the Big Bang Theory, Really?

Before challenging the Big Bang Theory, we must first understand what it actually claims. Contrary to popular belief, the Big Bang Theory does not assert that the universe began as a massive explosion in empty space. Rather, it proposes that approximately 13.8 billion years ago, all matter, energy, space, and time existed in an extremely hot, dense state. From this state, the universe began expanding rapidly, cooling as it grew, eventually allowing matter to form into the galaxies, stars, and planets we observe today.3

Importantly, the theory does not—and cannot—describe what happened at the exact moment of the “bang,” nor does it explain what existed before it, if anything. The mathematics of general relativity breaks down at what physicists call the “Planck time” (approximately 10^-43 seconds after the proposed beginning), creating a limit to our current understanding. The Big Bang Theory primarily describes the evolution of the universe from this point forward, not its ultimate origin.

The James Webb Challenge: When Observations Defy Predictions

The James Webb Space Telescope has delivered images of the earliest galaxies ever observed, dating back to just 300-500 million years after the Big Bang. According to standard models, these early galaxies should be small, chaotic, and in the process of formation. Instead, JWST found massive, well-structured galaxies that appear remarkably similar to those in our cosmic neighborhood.

Specifically, the telescope identified galaxies like GLASS-z13, which appears fully formed despite existing just 330 million years after the Big Bang.4 Another discovery, the Maisie’s Galaxy (GN-z11), shows a disk structure and chemical signatures that suggest multiple generations of stars had already lived and died within it—a process that should have required billions, not millions, of years.5

These observations challenge fundamental assumptions about how quickly matter could have coalesced into galaxies after the Big Bang. As Garth Illingworth of the University of California, Santa Cruz noted: “The models just don’t predict this… How do you do this in the universe at such an early time? How do you form so many stars so quickly?”6

These discrepancies don’t necessarily invalidate the Big Bang Theory entirely, but they do suggest that our understanding of early cosmic evolution may be incomplete or incorrect. This scientific challenge provides an opportunity to examine not just our cosmological models, but also the cognitive frameworks through which we interpret them.

Cognitive Biases and Scientific Misconceptions

Cognitive biases play a significant role in shaping our perception and understanding of scientific concepts. Two biases particularly relevant to our misconception of the Big Bang Theory are the bias for establishing a beginning and the narrative fallacy.

The Bias for Establishing a Beginning

Humans have an inherent tendency to seek out clear and definitive starting points or origins. This bias is deeply ingrained in human cognition and often leads us to oversimplify complex phenomena by attributing them to a single, identifiable beginning.

Consider the ongoing debate about when human life begins: Some argue it starts at conception, others at different stages of fetal development, and still others at birth. If there were an inherently existing, absolute starting point, we would have identified it definitively. Instead, different fields of study—embryology, neuroscience, philosophy, and religion—offer different perspectives because the concept of “beginning” itself is a conventional designation rather than an absolute reality.

Similarly, when contemplating the origins of the universe, this bias compels us to search for a specific moment that marks the absolute starting point. The Big Bang, with its dramatic name suggesting a singular explosive event, fits neatly into this cognitive preference.

The Narrative Fallacy

Our minds naturally organize information into coherent stories with clear beginnings, middles, and ends. This narrative fallacy influences our perception of scientific theories by compelling us to construct linear narratives that may oversimplify complex phenomena.

The Big Bang Theory, with its apparent narrative of a cosmic “explosion” leading to expansion and development, satisfies our desire for narrative coherence. Consequently, we often misinterpret it as providing a comprehensive explanation of the universe’s origins rather than what it actually describes: the evolution of the universe from its earliest observable state.

By recognizing these cognitive biases, we can approach scientific theories with greater nuance and precision, avoiding the misconceptions that arise from our natural cognitive tendencies.

The Influence of Religious Backgrounds on Scientific Thinking

Our cultural and religious backgrounds significantly shape how we interpret scientific theories. This influence becomes particularly relevant when examining how the Big Bang Theory has been received and communicated.

Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—have profoundly influenced Western intellectual traditions. These faiths share a common belief in creation ex nihilo—the notion that the universe was brought into existence from nothing through a divine act. This emphasis on a distinct starting point aligns perfectly with the cognitive bias for establishing beginnings that we discussed earlier.

When the Belgian priest and physicist Georges Lemaître first proposed in 1931 what would later become the Big Bang Theory, he described it as the “primeval atom” or “cosmic egg.”7 Interestingly, Pope Pius XII initially embraced the theory as scientific evidence for the Catholic concept of creation.8 Lemaître himself, however, cautioned against conflating scientific theory with religious doctrine.

This historical context helps explain why the Big Bang Theory has often been misinterpreted as describing the absolute beginning of everything. Scientists themselves, being members of society, may unconsciously present their findings in ways that align with dominant cultural narratives about origins.

This influence isn’t necessarily problematic—science is always practiced within cultural contexts—but awareness of these influences helps us distinguish between the empirical claims of a scientific theory and the philosophical or theological interpretations we might unconsciously impose upon it.

Nagarjuna’s Wisdom: A Philosophical Challenge to “Beginning”

Nagarjuna, the 2nd-century Buddhist philosopher and founder of the Madhyamaka (“Middle Way”) school, offers profound insights that directly challenge our notion of beginnings.9 His approach uses rigorous logic to examine how phenomena come into existence, ultimately demonstrating that the concept of an absolute beginning is logically untenable.

The Four-Cornered Negation: How Can Anything Begin?

Nagarjuna’s analysis employs what’s called the tetralemma or “four-cornered negation,” examining whether phenomena can arise in any of four possible ways:

- From themselves

- From something else (others)

- From both themselves and others

- From neither themselves nor others

Let’s explore each possibility using accessible examples:

1. Can Phenomena Arise from Themselves?

If a tree arose from itself, it would need to exist before it came into existence—a logical contradiction. If something already exists, it doesn’t need to begin. If a tree already existed as a tree, why would it need to arise again?

This is like saying a person gives birth to themselves—logically impossible because they would need to exist before they existed.

2. Can Phenomena Arise from Something Else?

This is our intuitive understanding: a tree grows from a seed; a child comes from parents; the universe emerges from the Big Bang. This view aligns with our conventional experience and forms the basis of most scientific and everyday explanations. However, when subjected to Madhyamaka analysis, this seemingly obvious position reveals profound logical problems.

Chandrakirti, elaborating on Nagarjuna’s work, devoted considerable attention to this very question, recognizing it as both the most intuitively appealing and the most philosophically problematic view of causation.10

First, let’s consider what “arising from something else” actually implies. For a phenomenon to truly arise from something else, both must be distinct entities with their own inherent nature or essence. The seed and the sprout would need to be fundamentally separate things, with the seed existing with its “seed-ness” and then somehow producing a sprout with its own distinct “sprout-ness.”

But this raises several logical problems:

The Problem of Temporal Relationship: If a sprout arises from a seed, we must ask: Does the sprout exist before its arising, during its arising, or after its arising?

- If the sprout exists before its arising, then it doesn’t need to arise at all—it already exists.

- If the sprout doesn’t exist before its arising, then how can a non-existent entity interact with the seed to facilitate its own production? A non-existent sprout cannot act upon or be acted upon by anything.

- If we say the sprout exists simultaneously with its arising, we’re essentially saying it exists as soon as it begins to exist—a tautology that explains nothing about causation.

The Problem of Continuity and Boundary: For a tree to truly arise from a seed (as completely separate, independent entities), we would need to identify the exact moment when the seed ends and the tree begins. But this is impossible—there is no precise moment when a germinating seed “becomes” a sprout. The process is continuous, with no clear boundary.

Consider a modern scientific parallel: embryonic development. Scientists, ethicists, and policymakers continue to debate when a developing human embryo “becomes” a person. Some argue for conception, others for the development of the neural tube, the detection of a heartbeat, the capacity for sensation, viability outside the womb, or birth itself. If there were an inherently existing boundary, we would have discovered it definitively. Instead, we find only conventional designations based on different criteria.

The Problem of Causation’s Mechanism: If seed and sprout are truly separate entities, what connects them causally? How does the seed’s cessation give rise to the sprout’s beginning? Chandrakirti points out that something that has ceased (the seed) no longer exists, so how can a non-existent entity produce anything? And if the seed hasn’t fully ceased when the sprout begins, then they exist simultaneously—but cause and effect are not supposed to exist simultaneously in this model.

The Problem of Essence Transfer: If phenomena arise from others, what exactly is transmitted from cause to effect? Nothing material from the seed becomes the sprout—the molecules are rearranged, energy is transformed, but no “essence of seed” transfers to become “essence of sprout.” Similarly, in physics, when an electron and positron annihilate to produce photons, what essential quality transfers from the particles to the light? The very concept becomes incoherent upon analysis.

Consider a modern scientific example: At what point does a collection of hydrogen atoms undergoing fusion “become” a star? Is it when nuclear fusion begins? When a certain temperature is reached? When it achieves hydrostatic equilibrium? Any boundary we draw is conventional, not absolute. The process is continuous, and our categorizations of “proto-star” and “star” are useful labels rather than reflections of inherently existing states.

Bringing this analysis to cosmology: If the universe arose from the Big Bang (as something inherently “other” than the initial singularity or quantum fluctuation), we would need to identify the precise moment when the “pre-universe” ended and the “universe” began. But just as with the seed and sprout, no such inherent boundary exists—only conventional designations applied to a continuous process of transformation.

3. Can Phenomena Arise from Both Themselves and Others?

If phenomena cannot arise from themselves alone or from others alone, they cannot arise from both combined. The contradictions of both positions would apply simultaneously.

This would be like saying a tree arises partly from itself (which would require it to exist before it exists) and partly from something else (which would require a definable boundary between seed and tree that cannot be found).

4. Can Phenomena Arise from Neither Themselves nor Others?

If phenomena arise from neither themselves nor anything else, they would arise without any causes or conditions—appearing randomly from nothing. This contradicts our observation that phenomena arise dependently on causes and conditions.

A tree appearing without seeds, soil, water, sunlight, or any other cause would be magical and contrary to all scientific understanding.

The Implications for Cosmic Origins

Having examined all logical possibilities for how phenomena can begin, Nagarjuna concludes that phenomena do not have inherent, findable beginnings. Instead, what we call “beginnings” are merely conventional designations applied to continuous processes of change.

When applied to cosmology, this reasoning suggests that the universe itself may not have an absolute beginning. Just as we cannot find the precise moment when a seed becomes a tree, we cannot identify an absolute moment when the universe “began.” What we call the “Big Bang” may be better understood as our current limit of observation within an ongoing, perhaps beginningless, cosmic process.

This philosophical perspective aligns surprisingly well with certain scientific models, such as cyclic universe theories or the “Big Bounce” hypothesis, which propose that our universe may be one phase in an eternal cycle of expansion and contraction.

Beyond Empirical Evidence: The Role of Logical Reasoning

While empirical evidence remains the cornerstone of scientific inquiry, certain questions about cosmic origins may lie beyond the reach of direct observation. No matter how powerful our telescopes become, they cannot see “before” the cosmic microwave background radiation that formed approximately 380,000 years after the Big Bang, let alone before the Big Bang itself.

Ancient Indian philosophical traditions, particularly those employed by Nagarjuna, recognized that logical reasoning can complement empirical evidence when investigating profound questions. His method of prasaṅga (reductio ad absurdum) skillfully exposes contradictions in our conceptual frameworks, leading us to refine our understanding.

Modern physics has similarly recognized the power of thought experiments and mathematical reasoning to explore realms beyond direct observation. Einstein’s theory of relativity, which forms the basis of Big Bang cosmology, emerged not primarily from experiments but from logical analysis of the implications of physical principles.

Interestingly, some contemporary cosmological models echo Nagarjuna’s insights. Loop quantum cosmology suggests that the Big Bang might represent a “bounce” in an oscillating universe rather than an absolute beginning. String theory’s landscape of possible universes and the concept of the multiverse both challenge the notion of a singular cosmic beginning.

By combining empirical observation with rigorous logical analysis, we develop a more nuanced and comprehensive approach to understanding cosmic origins—one that acknowledges both the power and limitations of human knowledge.

Alternative Perspectives: Beyond the Standard Big Bang Model

Several contemporary cosmological models offer alternatives to the standard Big Bang narrative that align with both the JWST observations and Nagarjuna’s philosophical insights:

The Big Bounce Theory

This model suggests that our universe may be one phase in an eternal cycle of expansion and contraction. Rather than beginning from a singularity, our universe may have “bounced” from a previous contracting phase. This cycle could be beginningless and endless, aligning with Nagarjuna’s critique of absolute beginnings.11

Eternal Inflation

Proposed by physicist Andrei Linde, this theory suggests that inflation (the rapid expansion shortly after the Big Bang) is eternal and continuously generates new “bubble universes.” Our observable universe would be just one bubble in an eternally inflating multiverse with no absolute beginning.12

Lombriser’s Static Universe Perspective

Lucas Lombriser has proposed a mathematical transformation of physical laws that reinterprets the observed effects attributed to cosmic expansion. In this model, the universe is not expanding but is instead flat and static, resembling Einstein’s Minkowski spacetime. The redshift and other phenomena traditionally attributed to expansion are reinterpreted as fluctuations in particle masses over time.13

These alternative models remind us that the Big Bang Theory, while supported by substantial evidence, is not the final word on cosmic origins. Scientific understanding continues to evolve as new observations challenge existing paradigms.

Conclusion: Embracing Cosmic Uncertainty

The James Webb Space Telescope’s discoveries have opened a window of opportunity—not just to refine our scientific models, but to reconsider the very way we conceptualize cosmic origins. By challenging our cognitive biases and enriching our scientific discourse with philosophical insights, we can develop a more nuanced understanding of the universe and our place within it.

Nagarjuna’s analysis suggests that seeking an absolute beginning may be misguided—not because the universe is eternal in a simplistic sense, but because the concept of “beginning” itself may be a conventional designation rather than an absolute reality. This perspective invites us to hold scientific theories like the Big Bang more lightly, recognizing them as useful models rather than definitive accounts of ultimate origins.

This is not to diminish the remarkable achievements of modern cosmology. The Big Bang Theory has successfully explained numerous observations, from cosmic microwave background radiation to the abundance of light elements in the universe. But like all scientific theories, it remains provisional and subject to revision as new evidence emerges.

Perhaps the most profound insight from both Madhyamaka philosophy and contemporary cosmology is that the universe may be far more mysterious and wonderful than our beginning-oriented minds can easily grasp. By embracing this uncertainty and continuing to question our assumptions, we open ourselves to deeper understanding and greater wonder at the cosmos we inhabit.

As we gaze through increasingly powerful telescopes into the depths of space and time, we may find that the question “How did the universe begin?” eventually transforms into “Has the universe always been becoming?” This shift—from seeking definitive origins to exploring continuous processes—may ultimately lead us closer to the true nature of cosmic reality.

Witze, A. (2022) ‘Four revelations from the Webb telescope about distant galaxies’, Nature, 608, pp. 18-19. doi: 10.1038/d41586-022-02056-5 ↩︎

Weinberg, Steven (2008). Cosmology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ↩︎

Peebles, P.J.E. (1993). Principles of Physical Cosmology. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ↩︎

Naidu, R. P., Oesch, P., Treu, T., and GLASS-JWST Team (n.d.). [Image/Data]. NASA/CSA/ESA/STScI. ↩︎

Álvarez-Márquez, J., Crespo Gómez, A., Colina, L., Langeroodi, D., Marques-Chaves, R., Prieto-Jiménez, C., Bik, A., Alonso-Herrero, A., Boogaard, L., Costantin, L., García-Marín, M., Gillman, S., Hjorth, J., Iani, E., Jermann, I., Labiano, A., Melinder, J., Meyer, R., Östlin, G., Pérez-González, P. G., Rinaldi, P., Walter, F., van der Werf, P., and Wright, G. (2025). ‘Insight into the starburst nature of Galaxy GN-z11 with JWST MIRI spectroscopy’, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 695, A250. doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202451731 ↩︎

NASA Webb Telescope Team (2022). ‘NASA’s Webb Draws Back Curtain on Universe’s Early Galaxies’ [Press conference]. NASA, 17 November. ↩︎

Kragh, H. (2012). ‘“The Wildest Speculation of All”: Lemaître and the Primeval-Atom Universe’, in Georges Lemaître: Life, Science and Legacy. Berlin: Springer, pp. 23-38. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-32254-9_3 ↩︎

Van Biezen, Alexander (2014). Between Religion and Science: Georges Lemaître, Pope Pius XII and The Big Bang Theory. ↩︎

Garfield, Jay L. (1995). The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way: Nagarjuna’s Mulamadhyamakakarika. New York: Oxford University Press. ↩︎

Padmakara Translation Group (2005). Introduction to the Middle Way: Chandrakirti’s Madhyamakavatara. Boston: Shambhala Publications. ↩︎

Ashtekar, A., and Singh, P. (2011). ‘Loop quantum cosmology: A status report’, Classical and Quantum Gravity, 28(21), 213001. doi: 10.1088/0264-9381/28/21/213001 ↩︎

Linde, A. D. (1986). ‘Eternally existing self-reproducing chaotic inflationary universe’, Physics Letters B, 175(4), pp. 395-400. doi: 10.1016/0370-2693(86)90611-8 ↩︎

Lombriser, L. (2023). ‘Cosmology in Minkowski space’, Classical and Quantum Gravity, 40(15), 155005. doi: 10.1088/1361-6382/acdb41 ↩︎